“If you figure a way to live without serving a master, any master, then let the rest of us know. For you’d be the first person in the history of the world.”

Every man has some things that trouble him to some degree, consciously or not. Doubts. Fears. Worries. Regrets. Desires. Things you don’t necessarily talk about, things you don’t even necessarily think about. Unless you get to a point where it’s just too much and it has to be expressed, one way or another. This often occurs after a high-stress or traumatic situation – the walls come down and suddenly a big old mess of emotions overwhelm you, which you’re then forced to either deal with, or bury again, or run away from…

This seems to be what’s going on with Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix) when we meet him, on a U.S. Navy ship coming back from the Pacific front of World War II. His behavior is slightly erratic and he spends an awful amount of time finding exotic ways of getting drunk, including by concocting booze using torpedo fuel… And then when’s he back on American soil, he keeps drifting between odd jobs and travels, punctuated by a series of breakdowns and screw-ups, some of which may be self-sabotage. Basically, he’s having a hell of a hard time readjusting to normal life, trying to fit in a post-war world.

“What a day. We fought against the day and we won.”

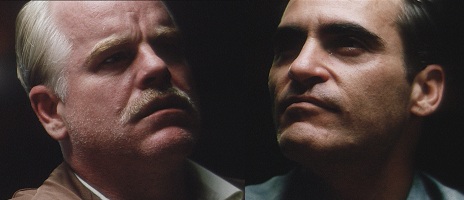

Enter Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a man who appears to be as confident as it gets. A man who seemingly has all the answers. A man with a way of quickly becoming the centre of attention in any gathering. And when he meets Freddie, he sees right through him, unveiling the vulnerability the young veteran hides behind an aggressively defensive exterior and pinning him down as a “hopelessly inquisitive man” and a “scoundrel.” But at the same time, Dodd finds Quell very familiar and through the course of the film, it will become increasingly clear that the two men are very much alike, even though they act in often very different ways. They’re mirror images of each other.

The Master is often being described as a movie about Scientology, but that’s way too reductive. It does show the way cults tend to work, but also the way religions and any cause, really, can take over someone’s life if they’re led by someone who abuses his power and if the believer is in an impressionable state.

“I can leave anytime I want, but I choose not to. I choose to stay here.”

But it’s not as simple as, one guy being evil and manipulative, and the other guy being an innocent victim. Writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson is way too wise and insightful to make it so black and white – his films always deal in gray areas, in nuances, in ambiguity. As such, we spend much of The Master wondering whether the titular character is a genius or a madman. Because some of what he says during his cryptic but deeply engaging speeches makes sense… Even though at times, it does feel like “he’s making all this up as he goes along.” It doesn’t hurt that he’s an extremely charismatic figure, thanks to a towering performance by Hoffman, who can come off like like a shark, a lion or any other predatory animal, yet with a lot of charm on top of it.

The scenes showing “sessions” or “processing” of people by Dodd are very interesting. It’s never explained, but you can understand how a system like this can get in people’s heads. Like, the person has to answer a series of questions without blinking, or to refrain from reacting to direct provocations… It’s basically forcing confessions out of people – and recording them. It must be a huge relief for the “patient” to get that shit off their chest, but then the “master” owns you, no?

“Pick a point and go at it as fast as you can.”

At some point, Dodd’s methods are compared to hypnosis and in a way, this is also true of what Anderson is doing. The Master is a film with a hypnotic, surreal quality. It can feel episodic, especially early on, but we later realize that it uses fractured storytelling – some pieces are missing and we get to them later on, through flashbacks or when Freddie talks about them during sessions. The film also seems to follow some kind of dream logic, sprinkled as it is with Is-this-really-happening? moments, e.g. the Master singing a song at a party where all the women are suddenly naked. Here’s an eminently unsettling and unpredictable picture, one where you never know where it’s going.

The Master features stunning cinematography by Mihai Malaimare Jr., with crisp whites, deep blacks and evocative use of color, thoroughly meticulous shot composition and lingering camera movements… Plus another bloody brilliant score from Jonny Greenwood which, like his There Will Be Blood music, is rivetingly eerie, often calling to mind the work Bernard Herrmann did with Hitchcock. Both the visuals and the music play a great part in giving the film its aforementioned hypnotic, surreal quality.

“We’re tied together.”

Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest is magnificent in every way, but I have to go back to the actors. The whole cast does stellar work (I should also mention Amy Adams as Dodd’s wife, who hides chilling darkness behind a sweet exterior), but both Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman outdo themselves in a spectacular way. I was particularly taken by a scene showing the two of them in the same frame but separated by a wall in the middle, Phoenix on the left and Hoffman on the right, the former completely out of control, kicking and screaming, and the latter almost perfectly still, trying to talk things through.

It’s primal emotions versus rational thought. A struggle as old as humanity. But of course, whether Dodd’s thoughts are actually rational remains questionable… There are no easy answers in The Master, which makes it all the more fascinating.