Penelope is a fairytale movie about a young bourgeois girl, born with a pig’s snout for a nose, on a quest for freedom from her overbearing family and alienating face. While at first the film’s lightweight plot and cuddly mood are disarmingly charming, things quickly start to lose steam and feel a little too familiar as Penelope borrows and channels the vision of many fairytale authors and fantasy film directors, but ultimately never finds its own.

From the very beginning director Mark Palansky boldly defines Penelope as a celebration of the classic folk tales as well as their gateway to the future by stylistically marrying the old fairytale cinematic language with the new. He clearly intends to do to live-action fairytale films what Shrek did to the animated ones: rehash, remix, and revamp the genre. However one cannot help but think of Tim Burton’s iconic imaging, especially with Christina Ricci, a long-time Burton collaborator, gracing the screen. From numerous shots of majestic trees with sinuous and leafless branches (Big Fish; Sleepy Hollow) to a decidedly over-saturated color palette (Charlie and the Chocolate Factory; Edward Scissorhands), it seems like Burton’s fingerprints are all over the film, consequently overshadowing Palansky’s own. There is no denying however, that Penelope ’s visual style, although plagiarized, is stunning, painting London and the title character’s home with a stroke of fantasy so vibrant and colorful that it makes the story seem out of this world.

In the same vain as Palansky’s directing, Leslie Caveny’s writing stands more as a mosaic consisting of deeply engrained literary classics than as an original piece. Considering that all fairytales generally encompass the same beliefs and value systems and have established a common repertoire of plot devices to fuel their analogous moralistic fables, similarities to previous tales are always to be expected. What Caveny fails to deliver however, is a fresh take that would allow the repetitiveness of such storytelling to be ingested obliviously and enjoyably by its audience. That being said, Penelope has its share of imaginative, funny and witty moments. The problem is that they all occur in the first act, leaving the second and third mostly devoid of humor. Comedy, the script’s only merit and sole redeeming factor, should have been Caveny’s main focus. Instead, the audience is entitled to sugarcoated dialogue and diabetes-inducing character arcs.

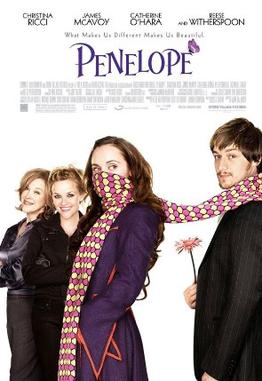

The acting in this film is, to say the least, colorful and effective. Ricci’s interpretation of Penelope is outstanding. She carries a lot of range as an actress and displays all of it in this film, going beyond the script’s limitations, and proving once again that she is a savvy and worthy leading actress. She paradoxically and effortlessly emotes naivety, jadedness, strength and vulnerability and captivatingly carries this movie from the beginning until the end. Ricci is so radiant and magnetic in this film that she even makes the snout look good. Furthermore, Catherine O’Hara miraculously manages to be likeable as the overbearing and superficial mother despite the incredibly annoying part she is given and Richard E. Grant holds his own very well as the guilt-ridden father. James McAvoy (Atonement) delivers what is required of him, but unlike the others, does not surpass any expectations and consequently feels more like a supporting actor than a leading man. The only true disappointment however, would be Reese Witherspoon (also a producer of the film) in a bit part as the eccentric and sarcastic friend. Seeming to rely mostly on the refreshing stunt casting rather than her acting, she delivers her lines with an unconvincing and one-dimensional cheekiness that falls flat real fast.

Penelope starts off as a cute and heartwarming film beaming with humor and charm, but ends up relying too much on the familiar and the comfortable, consequently clouding its vision with boredom and predictability. It is no wonder the movie has been on the shelves for over two years before its release, and maybe it should have been given even more thought before gracing theatre screens. That being said, Penelope could very easily be every little girl’s favorite movie until another one of its kind comes out.

Review by Ralph Arida